Recent efforts by the ACLU and SPLC to target municipalities for abuses of court fines and fees, as well as incarceration for non-payment are receiving national attention.

Civil rights lawyers are using a new strategy to change a common court practice that they have long argued unfairly targets the poor.

At issue is the way courts across the country sometimes issue arrest warrants for indigent people when they fall behind on paying court fees and fines owed for minor offenses like traffic tickets. Last year, an NPR investigation showed that courts in all 50 states are requiring more of these payments. Now attorneys are aggressively suing cities, police and courts, forcing reform.

Since September, six lawsuits were filed against New Orleans; Rutherford County, Tenn.; Biloxi and Jackson, Miss.; Benton County, Wash.; and Alexander City, Ala. In the past year, lawyers have also won settlements that have forced courts to change practices in Montgomery, Ala.; DeKalb County, Ga.; and St. Louis County, Mo.

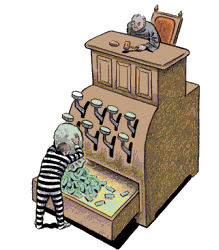

Biloxi is the latest city to be sued. Nusrat Choudhury, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union who filed the lawsuit, charges the city runs an illegal “debtors’ prison” when it puts indigent people in jail without adequately trying to determine whether the person has the means to pay court fines and fees or without then offering adequate alternative ways to pay off a fine, like being offered the chance to do community service.

Listen to the full story from NPR’s All Things Considered

Radley Balko writes about the debtor’s prison in Biloxi for the Washington Post

“Do the crime, pay the fine.” A little different, right? Many are unaware that when convicted of breaking the law, not only do people “pay” for their crimes by doing time, but they are also forced to pay up financially. The costs include court processing, defense attorneys, paper work, and anything else associated with their incarceration and supervision. In fact, anyone convicted of any type of criminal offense is subject to fiscal penalties or monetary sanctions. (If you have ever paid a traffic ticket, for example, you have paid a monetary sanction.) Further, the base fine of, say, a speeding ticket or even a major criminal conviction is just a small portion of the total cost. There are fines, fees, interest, surcharges, per payment and collection charges, and restitution. Until these debts are paid in full, individuals who have otherwise “done their time” remain under judicial supervision and are subject to court summons, warrants, and even jail stays.

“Do the crime, pay the fine.” A little different, right? Many are unaware that when convicted of breaking the law, not only do people “pay” for their crimes by doing time, but they are also forced to pay up financially. The costs include court processing, defense attorneys, paper work, and anything else associated with their incarceration and supervision. In fact, anyone convicted of any type of criminal offense is subject to fiscal penalties or monetary sanctions. (If you have ever paid a traffic ticket, for example, you have paid a monetary sanction.) Further, the base fine of, say, a speeding ticket or even a major criminal conviction is just a small portion of the total cost. There are fines, fees, interest, surcharges, per payment and collection charges, and restitution. Until these debts are paid in full, individuals who have otherwise “done their time” remain under judicial supervision and are subject to court summons, warrants, and even jail stays.